The “Fathers” of the Church are the leading figures/thinkers in the Early Church period. There is no agreed dating for this timeframe but it’s commonly considered to start after the New Testament texts were written and the twelve Apostles had died (around 100 AD) and continue until at least the Council of Chalcedon (451 AD) or the Second Council of Nicaea (787 AD). Oh, and just to clarify, the “Desert Fathers” are a subset of the Fathers who lived a monastic life, either individually or in community (and often in the desert!).

During this period, the Roman Empire was divided into West and East with often not just different emperors, but also crucially quite different language/mindset/philosophical backgrounds. The Western half was rooted in the Latin language and mindset, and the Eastern rooted in the Greek. As time went on, the Churches (and key thinkers) located in the West or East therefore did their thinking and theology (and had their life experiences) in different contexts, and with quite different assumptions, and results.

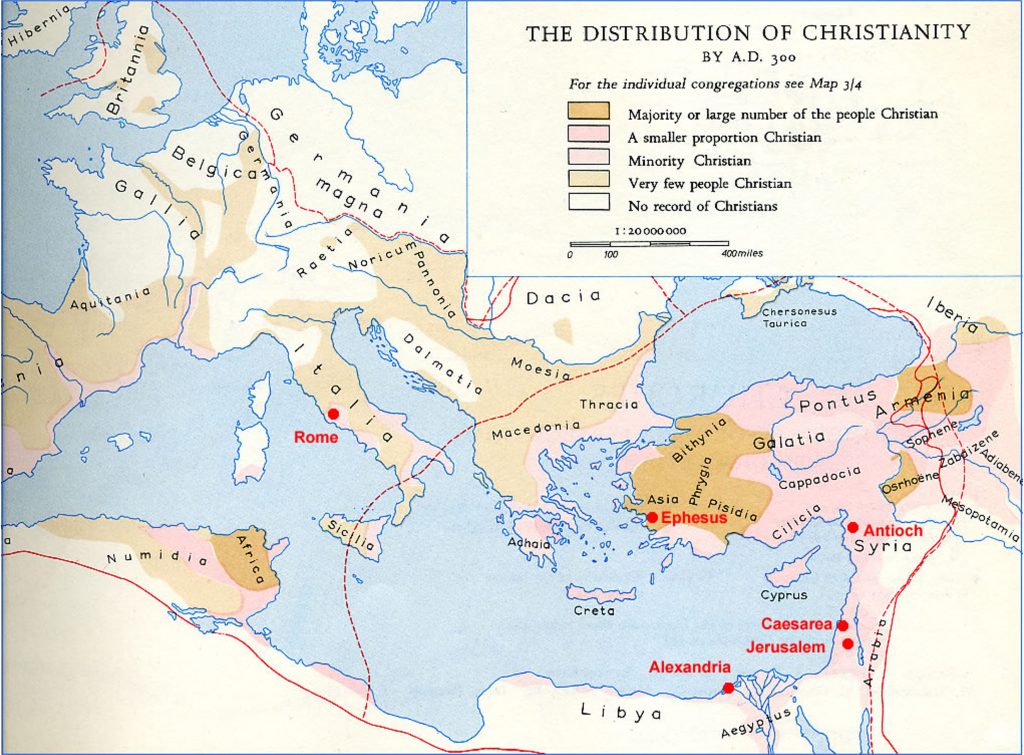

Time for a map showing The Distribution of Christianity by AD 300. The eagle-eyed will notice the absence of Constantinople (modern day Istanbul) as by that point the emperor Constantine had not yet become sole emperor of the Roman Empire (324 AD) and made it his “ople” (330 AD). It’s also worth noting that the severe persecution under the emperor Diocletian came to an end in 311 AD, so this map doesn’t reflect the further significant growth that happened during the 4th century (under the sponsorship of Constantine and other subsequent emperors).

The diagonal dotted line that starts at the bottom of the map in North Africa, cuts through Sicily and the boot of Italy and appears above Macedonia and Thracia, is a rough indicator of the West/East split.

The early thinkers of the Western Church include figures such as Tertullian, Cyprian, Jerome, Augustine of Hippo, whilst in the East prominent names include Irenaeus (although “of Lyons”, he was born in Turkey and wrote in Greek), Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Athanasius, Gregory Nazianzus, Gregory of Nyssa, St Basil the Great, John Chrysostom and Cyril of Alexandria.

The Western inheritance fed into what would evolve and crystallise into the Roman Catholic Church (from which the various Protestant denominations subsequently “protested”) whilst the Eastern inheritance fed into what would become the Orthodox Church(es).

So why the explicit focus on the Eastern Fathers in the strapline and content for this website? Essentially because as a Westerner (living in the UK and with a Protestant background), encountering the thought of the Eastern Fathers has been a huge source of personal inspiration. I think this is for two reasons.

Why the Fathers?

Because the world of the Fathers is so long ago (and crucially, pre-Enlightenment) their way of understanding, wrestling with and “knowing” things is quite different from the contemporary post-Enlightenment world. We live in a very scientific and technologically driven age (not that I’m complaining – I have a degree in Chemistry, work in IT and very much appreciate tools and toys such as my iPhone and Mac as well as the advances and benefits of science and medicine).

However, I think the success of this way of thinking has led to what I’d call (in an unusual flourish of fancy rhetoric) the “Hegemony of Enlightenment Epistemology”. Which is my attempt to find a clever way of saying “the ONLY way to know & understand ANYTHING is in an Enlightenment stylee” (double ee added deliberately for comic effect). The Enlightement/Scientific approach is to “atomise to understand” – you (individually) smash things apart, look for the elements and components, start from the (physical) evidence – essentially you reduce things down. This works fantastically well for Chemistry, Physics, Geology or tracking down bugs in software. And, usefully, we now understand a lot about how things work.

But when you apply this approach to a question like “What is a person?” you end up with merely a compositional answer, as found on Wikipedia…

“About 99% of the mass of the human body is made up of six elements: oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, calcium, and phosphorus. Only about 0.85% is composed of another five elements: potassium, sulfur, sodium, chlorine, and magnesium. All 11 are necessary for life. The remaining elements are trace elements, of which more than a dozen are thought on the basis of good evidence to be necessary for life”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Composition_of_the_human_body accessed on 20th October 2023

… but I’m not sure that’s a good (enough) answer for what I am, or what you are, or the differences between us. And if you just scraped together those elements and mixed them up in a bucket, you wouldn’t spontaneously create any sort of person (let alone me). That, to me, is a mystery and the kind of complexity that I’m interested in wrestling with. Suddenly the ability to decompose things into their elements doesn’t seem as impressive as it once did. I increasingly find that the questions I want to grapple with are the ones that involve complexity, not reduction.

My concern is that I think this approach (because it’s been so successful in a number of key areas) has become so culturally embedded that it is now perceived to be the only way to “know” and understand anything. And I don’t think that works for quite a few things. Like people, or art, a play, poetry and yes, theology. Of most concern is that I think this can have a (largely unexamined) impact on the way that our “ordinary theology” is done (by which I mean the way that the person in the pew does their theology – because, following Jeff Astley, I believe we all “do theology”, whether we acknowledge it or not).

Since the Fathers lived and worked in a time before Enlightenment thinking had become embedded as the ONLY way to approach anything, they are free from the assumptions that come with it, and have a different perspective. In his (thought provoking) introduction to a classic text (“On the Incarnation“) by one of the Eastern Fathers (St Athanasius), C.S. Lewis makes this point very well…

“Every age has its own outlook. It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period. And that means the old books. All contemporary writers share to some extent the contemporary outlook – even those, like myself, who seem most opposed to it.”

C.S. Lewis in Athanasius, & Behr, John. (2011). On the Incarnation (St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press Popular patristics series; 44a). Yonkers, N.Y., p.12

He goes on to say “It is a good rule, after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between. If that is too much for you, you should at least read one old one to every three new ones”. Lewis advocates reading the classics (such as “On the Incarnation“) in order to provide perspective, because (despite how clever we have become in our Enlightenment approach) there’s nothing especially privileged about the context in which we as ordinary theologians think.

One insight I gained from reading the Fathers was to understand that Theology is not something that is approached purely through reason. It is not an Enlightenment science. It is not (just) logical. It is theo-logical. The rules are different. I’ll blog about this further, but one of the suggestions I’ll make is to read how another of the Eastern Fathers (St Gregory of Nazianzus – “The Theologian”) explains theology. He does this in a set of five speeches (orations) collectively referred to as his “Five Theological Orations“.

In this text he sets out to explain and defend the doctrine of the Trinity, but before he gets there he occupies himself in the first oration (number 27) with the nature of theology and the task of the theologian. In this oration he takes aim at his opponents (sometimes called the Neo-Arians) and refers to them as “technologians”. He accuses them of being ultra-rational in their understanding of God, they’re techno-logical not theo-logical. It’s my suggestion that today’s ordinary theologians (“living, moving and having our being” in a cultural context so dominated by unexamined Enlightenment way of seeing everything) might be in similar danger of trying to do their thinking in a way that’s too (purely) logical and not (fully) theological and coming to some odd conclusions. So that’s why the Fathers.

Why Eastern?

In short, because the viewpoint of the Eastern Fathers on some key topics is quite different from that found in contemporary Western Christianity. And, to put it very bluntly and plainly, because their God is nicer. Whilst the Fathers of the Church may have been geographically distributed in the East or West, they are the shared inheritance of the Church (as they flourished before the split between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches in the “Great Schism” of 1054).

Christianity is in significant decline in the West for lots of reasons (I would even venture to say, perhaps some of them good ones?). I believe that a return to the perspective of the Eastern Fathers (with their quite different views on some key topics) can be a source of inspiration to the contemporary Western Church. A brief sketch of some of these topics is provided below, but the Study Days offered via this website go into a little more depth.

Importantly, I’m not going to contrast the views of the Eastern and Western Fathers, or even the East and West contemporary churches, because I’m simply not qualified to do so. But I am qualified to say something about the difference between what I was “taught” (or rather picked up by osmosis in the liturgy, worship, sermons etc) in contemporary Western churches vs what I have encountered in the Eastern Fathers.

Theological Anthropology

Let’s kick off with what sounds like one of those really technical terms, but which in essence is quite simple. How to understand what it is to be human in relation to God, from God’s perspective if you like. And in this area, the East is quite different from the West. When it comes to Human nature it’s a classic case of glass half empty or half full.

Except, from the Western perspective I encountered, my glass was not even half full. There’s pretty much nothing in it. Maybe some drops left at the bottom, but even that is in serious doubt. The Book of Common Prayer is keen to remind us of this and has us say “there is no health in us” (Book of Common Prayer, General Confession in Morning and Evening Prayer). And in the Prayer of Humble Access we say “We are not worthy to gather up the crumbs under your table… that our sinful bodies may be made clean by his body”. There’s a definite emphasis on “look at what you’re not“.

A famously negative (Western) take on what it is to be human can be found in Augustine, with his concept of “Original Sin” (perhaps more accurately labelled as “Original Guilt”) which might be understood as some kind of ontological infection – it’s in your DNA. We inherit Adam’s sin and guilt, we are born in sin, and therefore (logically) unbaptised babies that die go to hell.

I was also taught that when it comes to the grace of God, this is an overpowering and “external” force. Whilst there is a grudging recognition of human free will, this is more of a technicality because this faculty has been fatally damaged. We are unable to exercise free will (unaided) so can’t even choose salvation – it is a gift of God. The result is predestination (we all deserve damnation, only the lucky few get in, it’s all been decided already).

What I discovered in the Eastern Fathers is the complete opposite. For them the glass of my humanity is half full – there is some hope, some potential. The emphasis is on “look at what you could be!”. I think this comes from their deep seated belief in each of us being made “in the image of God”. Whilst this image-ness (or likeness) may certainly be damaged, it is still present. The Eastern Fathers absolutely have a sense that human nature has changed for the worse after Adam, and the consequence is death and corruption. But there is no concept of inherited “Original Guilt”. And however bad things get, the Image remains. Grace is not just external but also in some sense internal by virtue of our being made by God.

If human nature was a stick of seaside rock, when cut open, my contemporary Western “education” told me the writing said “sin”, but the Eastern Fathers taught me it instead says “Image of God”. Commenting on “If you know not yourself, beautiful one among women, go in the footsteps of the flocks, and feed the kids by the shepherds’ tents.” (Song of Songs 1:8) Gregory of Nyssa writes…

In order that you do not suffer misfortune, watch over yourself as the text says. For this is the surest way to protect your own good; realise how much more than the rest of creation you are honoured by the Creator. He did not make the heavens in his image, nor the moon, sun, the stars’ beauty, nor anything else you see in creation.

Commentary on the Song of Songs, Homily 2 (McCambley, pp.70-1)

You alone are made in the likeness of that nature which surpasses all understanding, the image of incorruptible beauty, the impression of true divinity, receptacle of blessed life, seal of true light. You will become what he is by looking at him. By imitating him who shines within you [2 Cor 4:6], his gleam is reflected by your purity. Nothing in creation can compare to your greatness.

All of heaven is contained in the grasp of God’s hand, and the earth and sea fit in the palm of his hand. Although he holds all creation in his palm, you can wholly contain him. God dwells in you, penetrates you, and is not confined in you. He says “I will dwell in them, and walk with them” [2 Cor 6:16].

If you consider this, you will not let your eye rest on any earthly thing, nor will you consider heaven as marvellous. How can you admire the heavens, O man, seeing that you are more enduring? They pass away [Mt 24:35], but you remain for eternity with him who always exists.

When it comes to free will this is also a point of emphasis in the East and is a direct consequence of being made in the image of God. We have been given the power to choose the good (or the not-good). We have the power of self-determination, and we need to exercise it – otherwise where is virtue? There is no place for praise or blame for choosing a good/bad path if you actually lack genuine free will in the first place. We are not utterly powerless and our free will is efficacious.

I am not of course saying that we save ourselves through our own efforts. But neither are we mere passengers on the journey of salvation – we have a part to play. Surely this is the meaning of “work out your salvation with fear and trembling” (Philippians 2:12).

Gregory of Nyssa is also one of my favourite authors on this topic. His writings display a clear understanding of the reality of our imperfect nature, but also revel in our created potentiality as image-bearers. He sees the spiritual life as one of Synergy (co-working) with God…

For the grace of the Spirit gives eternal life and unspeakable joy in heaven, but it is the love of the toils because of the faith that makes the soul worthy of receiving the gifts and enjoying the grace. When a just act and grace of the Spirit coincide, they fill the soul into which they come with a blessed life; but, separated from each other, they provide no gain for the soul.

On the Christian Mode of Life in V. Callahan (trans), St Gregory: Ascetical Works – Fathers of the Church Vol. 58 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1967), pp.131-2

For the grace of God does not naturally frequent souls which are fleeing from salvation, and the power of human virtue is not sufficient in itself to cause the souls not sharing in grace to ascend to the beauty of life. For it says: ‘Unless the Lord build the house and keep the city, he labours in vain that builds it and watches in vain who keeps it.’ And again: ‘For not with their own sword did they conquer the land; nor did their own arm make them victorious (although they used their swords and arms in their struggles), but it was your right hand and your arm, and the light of your countenance.’

What does this mean? It means that the Lord from on high enters into an alliance with the doers, and, at the same time, it means that it is not necessary for men considering human efforts to think that the entire crown rests upon their struggles, but it is necessary for them to refer their hopes for their goal to the will of God.

The Eastern Church also has a kinder take on the myth of the Garden of Eden. In The Story of Original Sin, John E. Toews writes…

“[For the Eastern Church] shaped by the theology of Irenaeus… the disobedience of Adam and Eve was a result of child-like immaturity rather than wilful intention. There is no such thing as “original sin” or “inherited guilt”. Sin is always a personal act, never a function of nature.”

John E. Toews, The Story of Original Sin (Pickwick Publications, 2013), p.88

For Irenaeus, Adam was a child whose failure was to grasp too soon for what was promised, not a perfect being who “fell” from perfection. Toews provides the following summary…

“Adam’s first sin was one of thoughtlessness rather than of malice. The primary blame for Adam’s misstep rests with the devil who acquired power over him unfairly, by a trick. It is not surprising that Irenaeus did not attach a high degree of guilt or culpability to Adam’s sin. God pitied, rather than condemned, his frail, imperfect, inexperienced creature for succumbing to the wiles of a cunning and powerful foe. The sin of Adam was far less serious than Cain’s. Adam’s transgression, though not an infection transmitted to subsequent generations, did lead to death, which Irenaeus also interpreted as a divine mercy.”

John E. Toews, The Story of Original Sin (Pickwick Publications, 2013), p.53

And it’s this positive disposition to his creatures in their fallen state that is another characteristic that shines through in Eastern theology. God does not have to be begged for mercy like a bully or a judge, but rather is already pre-deposed to rather quite like us. The word often used in Eastern texts in connection with this is the “philanthropy” of God. This sounds odd to Western ears as we’re more used to it being applied to generous financial benefactors. But the English word is a translation from the Greek and literally means “lover of humanity”. God does not hate anything that he has made.

Salvation, Incarnation and “Humanification”

The more I read, the more I’ve come to realise that salvation in the West seems to have taken a very odd turn over the past 1,000 years. The models and metaphors used (e.g. Satisfaction and Substitution, – culminating in Penal Substitution) have all been about a transactional approach to averting or appeasing the wrath (or the damaged honour) of a King or feudal Lord.

The problem of course is that these days we lack a feudal structure for society and there’s a growing lack of interest, let alone respect, for the monarchy (assuming of course that you live in a country that still has one). So the metaphors/models and language used in Western churches to try to explain what is wrong with humanity and how Christ rescues us (called “soteriology”) is completely out of step with contemporary society. There is what I would call “Cultural Soteriological Dissonance” at work.

In my reading of the Eastern Fathers they don’t see the need for punishing atonement. Instead, they’re mesmerised by the Incarnation (which they see as the “Humanification” of God, and the resulting transformation of humanity). The Eastern Fathers teach me that it is in the totality of Christ (his birth, growth, life, teaching, miracles, death and resurrection) that salvation is found.

I find the contemporary Western Church (or at least the examples I’ve encountered) to be focussed almost entirely on the Cross as the locus of salvation – there is a “Crucifixation”. As soon as Christ is born at Christmas, there’s a rush to the Cross. But he lived 30+ years of an (ordinary) human life and in this there is also salvation (see the About page for a quote from Irenaeus on this subject).

Paradox & Mystery

What’s also striking about the Eastern Fathers is the degree to which they’re comfortable with, or even revel in, paradoxical thinking. That’s pretty handy because the resolution to various debates on the Incarnation, Christology and the Trinity which arose in the Early Church period all fundamentally require paradoxical thinking. And where there’s paradox, there is also mystery (which is not to be understood as just some kind of complex problem that we’ve not yet solved… but will one day).

After a few hundred years of reductionistic, scientific materialism I think there’s a renewed appetite culturally for paradox (especially since science itself these days requires paradoxical thinking e.g. Wave-particle duality in quantum mechanics). Christian apologetics, at least in some circles, has been keen to show the rationality & reasonableness of faith. But maybe it’s time to embrace the paradoxical and mysterious once again with renewed confidence? If so, the Eastern Fathers can help get you in the mood.

Beautiful Allegorical Exegesis

From paradox & mystery to exegesis. In a superb book Discerning the Mystery: An Essay on the Nature of Theology, Andrew Louth makes the case for a renewed appreciation of the exegetical approach of allegory (as used by figures such as Origen and Gregory of Nyssa). Louth points out the resonance between post-modern reading of texts and the allegorical method used by some of the Fathers, and explains the intention behind the use of allegory…

“It is important to realize this: that the traditional doctrine of the multiple sense of Scripture, with its use of allegory, is essentially an attempt to respond to the mira profunditas of Scripture, seen as the indispensable witness to the mystery of Christ. This is the heart of the use of allegory… We are not concerned with a technique for solving problems but with an art for discerning mystery.”

A. Louth, Discerning the Mystery: An Essay on the Nature of Theology (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983), pp.112-3

A couple of classic examples of allegorical exegesis can be found in the works of Gregory of Nyssa – the Life of Moses and Homiles on the Song of Songs – see the page on Gregory of Nyssa for details. Gregory’s playful, creative, inspired & mystical wrestling with the text is wonderful to read and might be just the shot in the arm you need if you’re struggling with dry, rational explanations of scripture.